2014 Fundraising Campaign Begins

We are excited to announce a new fundraiser campaign for 2014 and invite our patrons to visit our secure online donation page and make their contribution towards Kutumb.

For those of our supporters who are in NY-NJ-PA-CT area, we are holding a Benefit Concert on Nov 22nd in Jersey City, NJ. This is a great way to meet, interact and learn more about Vision Builders and Kutumb. We hope you will join us to enjoy a fun musical evening and send our collective wishes and support to children at Kutumb.

Your generous donations during BEAT THE BALL DROP in 2013 raised: $26825.00 for Kutumb, and every cent went directly to the Kutumb programs which directly impact the lives of children!

To stay up to date, visit Vision Builders Facebook page, and “Like” us so you can follow the exciting progress in your news feed!

Vision Builders Invites you and your family to a Benefit Concert

5:30pm on Saturday, 22nd November, 2014

VENUE: The Duncan Family Sky Room @ The Mac Mahon Student Center

located on the 6th Floor,

Saint Peter’s University,

782 Montgomery street,

Jersey City, NJ 07306

Program Schedule

5:00pm: Doors Open, Check-in

5:30pm: Cocktail Reception (with Cash Bar)

6:00pm: Concert

Our First Outreach Event in New Jersey

We had a successful first event in NJ. Vision Builders participated in Sanskriti India Day held in Livingston, NJ on Sunday, June 8th.

Many thanks to our latest volunteer, Ahir Verma, who spearheaded the campaign for this event. Ahir also helped prepare the marketing materials for this event. This event greatly helped raise awareness for Vision Builders and our Project Kutumb. We raised some much needed funds as well. Thanks for everyone’s support and we look forward to connecting again in near future.

Vision Builders Office Relocates to New Jersey

In 2013, Vision Builders began partnering with Arun Verma and Smita Abbi of New Jersey. Arun and Smita are dedicated to the Vision Builders mission, and played an integral role in our 2013 “Beat the Ball Drop” fundraiser. We are very excited to announce that the Vision Builders U.S. office has now relocated from Michigan to New Jersey, where Arun and Smita reside. Arun and Smita will now lead the Vision Builders organization, along with their newly appointed Board of Directors, and will continue the work to support Vision Builders’ ongoing mission.

Please welcome the new Vision Builders Board of Directors:

Smita Abbi

Chandan Banerjee

Kumarika Banerjee

Tavish Bahl

Bhanu Bahl

Mary Ann (Shaleena) Koruth

Bini Mammen

Arun Verma

Let's Beat the New Year Ball Drop!!

MATCHING DONATION!

Every single dollar that you donate makes a difference,

AND NOW EVERY SINGLE DOLLAR DONATED WILL GO TWICE AS FAR!

Our sincerest thanks to supporters Smita Abbi and Arun Verma of Greenbrook, New Jersey. Who have generously pledged a 1:1 match on Beat the Ball Drop donations received by Vision Builders, to help us meet our fundraising goal!

Just click on our Donate Now button, and your donation will automatically qualify for a 1:1 match.

Don’t forget that our fundraising deadline is by midnight on New Year – before the ball drops!!

BUT THERE IS NO NEED TO WAIT – you can Donate Now!

Read our latest eNewsletter for more information! Vision Builders eNews_Winter2013

Introducing Katie Kirkpatrick, Board President

Katie Kirkpatrick, Vision Builders Co-Founder and Board President

Katie and her husband have both been involved with charitable projects for most of their lives, and the idea for Vision Builders took fruit when they traveled to India and Nepal on a Buddhist pilgrimage with their oldest daughter, who was seven at the time. Their youngest daughter was not yet born, but has since traveled with Katie to Varanasi, India and the Nadasar slums to visit the Kutumb project, which is supported by Vision Builders. When we asked Katie about the beginnings of Vision Builders, this is what she shared with us:

“… As we walked through Kathmandu and Nepal and the cities of India, the street children all come around you with their hands out, and my seven-year-old would look at me and she’d say ‘Mom, do these children have a home? Mom, look how dirty they are. Mom, they want food.’  I was watching other tourists deal with this and most people would just continue walking, making no eye contact… acting as if no one was begging in front of them. That is one way that people deal with this issue, but as a parent I couldn’t really say to my seven-year old daughter ‘Oh, pretend you don’t care about these begging children.

I was watching other tourists deal with this and most people would just continue walking, making no eye contact… acting as if no one was begging in front of them. That is one way that people deal with this issue, but as a parent I couldn’t really say to my seven-year old daughter ‘Oh, pretend you don’t care about these begging children.  Don’t look.’ That’s the strategy that a lot of people who go there, especially as tourists, adopt in order to deal with these masses of begging children.

Don’t look.’ That’s the strategy that a lot of people who go there, especially as tourists, adopt in order to deal with these masses of begging children.

…I think that most of us come from cultures where there’s a homeless shelter, where there are organizations providing food, or there’s some way that help is being provided. But that is not true in this part of the world. So it presented a little bit of a problem when we’d have these conversations and my daughter kept saying ‘Well, what can we do? What can we do?’

…we went into the hotel and I asked them to make 60 hard-boiled eggs. We would buy 60 hard-boiled eggs from the kitchen and we would go out and hand the children hard-boiled eggs. It was something nutritious that we could just put in their hands, they were thrilled! That might be the only food they had that day.

…I had brought along a bottle of chewable vitamins for my daughter. And she said, ‘I don’t really need vitamins because I have plenty of good food. So, can we give the vitamins to the children?’ So we started handing out chewable vitamins to the children. Increasingly it was just an issue of – we can’t look away. We’re not the kind of people who can look away. We were so touched by the situation and the circumstance, and what we learned over time is that just putting your hand in the child’s hand and giving them a smile was even enough. Just acknowledgement. ‘Yes, I see you. You exist and I don’t have anything on my person to give you but I can give you this moment where we connect and I care about you.’ So personally, I found that really moving. And I came back and decided I had to do something, because I couldn’t do nothing.”

When asked if she thought that apathy is the hardest thing to overcome in these situations, Katie replied that, she doesn’t think it’s so much apathy as it is being overwhelmed. “I think when people go to India and they see the level of poverty, they just think ‘Well how could I possibly have an impact on it?’.” The project that Vision Builders is currently working with is called “Kutumb”. It’s in Varanasi, India, which is the most ancient consistently-inhabited city in the world. Katie describes it as being “so beautiful in so many ways, and so ugly in so many other ways” – 40% of the millions of people in Varanasi live in abject poverty.

“…There are just huge areas, everywhere you look, people are living in slum conditions. They’re making makeshift houses out of pieces of cardboard or plastic tarps. They’re making a living by collecting trash. They pile it up on a bicycle, 8 feet high, tying it with ropes and bringing it back into the area where they live, to burn it.  So there’s just burning trash everywhere. There’s broken metal and pieces of glass – it’s just really shocking. I have taken two of my friends, who work for Vision Builders, to Varanasi on my annual trip. And, as much as I’ve told them about the area where the project is, they still get off the plane and say, ‘I had no idea.

So there’s just burning trash everywhere. There’s broken metal and pieces of glass – it’s just really shocking. I have taken two of my friends, who work for Vision Builders, to Varanasi on my annual trip. And, as much as I’ve told them about the area where the project is, they still get off the plane and say, ‘I had no idea.  Oh my gosh, I had no idea’. From a Western perspective, it is mind-boggling. The size of the slum area, and the sheer number of people living in these conditions are enormous. So I don’t think it’s apathy, because most people who see those conditions would want to do something to help, but there’s so many challenges.

Oh my gosh, I had no idea’. From a Western perspective, it is mind-boggling. The size of the slum area, and the sheer number of people living in these conditions are enormous. So I don’t think it’s apathy, because most people who see those conditions would want to do something to help, but there’s so many challenges.

…You also want to make sure that you are actually being helpful rather than creating new problems. I’m reminded of Oprah talking about founding her school in Africa, and one of the first things she did is give the children extravagant gifts, like Nike shoes or iPods or whatever. But she came to understand that this was a mistake. That’s not what they really need, and it just causes them to become materialistic when they’ve never been materialistic before. So you really want to make sure that whatever money you’re giving is having a positive impact. You want to make sure it is going to a person who really knows what the problems are, and has ideas and actual solutions for those problems. You need a person of integrity, a person you can really count on, and my experience is that that is rare and hard-to-find.”

Katie says that they started small, and learned over the years what works and what doesn’t.

“Really, what works is food, education, healthcare and women’s empowerment. Women’s empowerment is an important factor in these circumstances because if you teach a woman to read she will teach her children. If you teach a man to read, he may be able to get a little better job, but he won’t teach his children. I don’t quite understand it myself, but I’ve been reading about this a

“Really, what works is food, education, healthcare and women’s empowerment. Women’s empowerment is an important factor in these circumstances because if you teach a woman to read she will teach her children. If you teach a man to read, he may be able to get a little better job, but he won’t teach his children. I don’t quite understand it myself, but I’ve been reading about this a  lot. I see the fathers in this area, and most of them are very caring and involved with their children. But statistic shows that empowering women is what makes an impact.

lot. I see the fathers in this area, and most of them are very caring and involved with their children. But statistic shows that empowering women is what makes an impact.

…Dr. Ashish, my partner in India who runs Kutumb, incorporated a women’s empowerment program into their work. The program includes activities like taking the women to the post office and explaining to them how the post office works. Or, taking them to the bank and explaining how bank accounts work  and how they can set up a bank account. Very basic things, to us, but this is the beginning of what makes it possible for them to start very small businesses – making and selling teddy bears, for example, in the open market. With these basic skills they can make even just a small amount of money to support their families. He [Dr. Ashish] has all kinds of programs for women, teaching them to read if

and how they can set up a bank account. Very basic things, to us, but this is the beginning of what makes it possible for them to start very small businesses – making and selling teddy bears, for example, in the open market. With these basic skills they can make even just a small amount of money to support their families. He [Dr. Ashish] has all kinds of programs for women, teaching them to read if  they’re interested in reading, teaching them to cut hair… Most of the women, prior to attending his programs, have never left the slum area where they live. They’ve never gone outside of it because of fear, so their lives are very small. And by having these women’s empowerment programs, it opens up their lives and also their possibilities.”

they’re interested in reading, teaching them to cut hair… Most of the women, prior to attending his programs, have never left the slum area where they live. They’ve never gone outside of it because of fear, so their lives are very small. And by having these women’s empowerment programs, it opens up their lives and also their possibilities.”

Basic nutrition is, of course, vital. One morning Katie went to a family’s house, made of plywood and tarps, and they were serving breakfast. Each of the children was given the equivalent of a quarter cup cooked lentils. That was their breakfast. Yet everyone was smiling and happy and chattering away. “It was just so shocking to me”, said Katie. “That was breakfast? To you and me that wouldn’t even qualify as a snack for children.”

“…A tiny bowl with a quarter cup of cooked lentils, that was breakfast. So we started a program at Kutumb where any child in the vicinity who wants to come to the shelter is fed breakfast and lunch. Now they can come and they get a balanced meal. They get fruit, they get milk. Most of them are vegetarian, so it’s a vegetarian meal cooked with love. And it’s just been phenomenal to see the children blossom. Children who previously were really sickly and malnourished – they now come to the shelter and they eat two good meals a day, and whatever else their parents can give them. And they are more alive, they are more embodied, they are doing better at school. Because how can you pay attention at school when you’re literally starving and malnourished?”

The project in Kutumb is run by this fellow Dr. Ashish and his wife Puja. They’re both in their early 30s, along with Puja’s younger brother Vivek, and his wife Swati. The four of them basically take care of all of the bookkeeping and the decision-making in the programs and finding the resources.

“…They are amazing people. In the six years that Vision Builders has been involved with them, I can honestly say they’re the people of highest integrity I have ever met. There is nothing suspect about them. I have visited them four times, for two weeks at a stretch. And every time I go, I think ‘I hope we don’t run into any uncomfortable issues about ‘where did this money go?’ or ‘what happened here?’, but there has never been an issue. They keep in touch regularly. I hear from them every week via email and we have phone calls. And sometimes we Skype. They are so positive and so willing. They are 24/7 + 40 more hours that I don’t know where they come from! It’s just wild what they’re able to accomplish. They never stop moving, and doing, and I feel so excited about them because they have a lot of years ahead of them to continue what they’re doing. When I come and we sit down and we look over the books, everything is meticulously organized and laid out. They are always positive, grateful – just so appreciative. But not in a way that is at all obsequious. For example, if I have an idea and they don’t think it will work or they’re not sure it’s a good idea, we’ll have a really honest discussion. They’re not just trying to placate me or please me. And I think that’s such an unusual quality because usually when you’re receiving funds from someone, you feel some sense of obligation to appease them in some way. And I’m so grateful that they don’t do that.”

The amazing thing about this project is that, even in the midst of so many challenges, there are success stories coming out of this. The children are getting healthier and going to school, and the women are developing life skills and finding work.

“… the first year that I visited Kutumb, there was a little girl there named Geeta who was nine years old. At that time I was traveling with my younger daughter, who was also nine. Geeta had just arrived a week prior. They found her in a railway station that’s adjacent to the slum. She was sitting on the floor of the railway station, sobbing because her mother had died from a snakebite. They had lived in the railway station, begging. Her mother’s body was hauled away by the city to burn. Geeta had just been left with her younger sister, who was three years old. This nine-year-old had fallen asleep and her sister had disappeared. She was beside herself. Dr. Ashish and Puja found her. Puja goes to the railway station and makes the rounds every day to look for children who have been abandoned, or whose parents have died. And so they found Geeta in the railway station. They took her back to Kutumb, they contacted the police, put up signs, and went around with a group of people asking if anyone had seen this younger sibling, but the little girl was never found. Geeta has lived at Kutumb now for three years. When she first arrived and I first met her, she was very guarded. At one point, I put my hand on her shoulder and she snapped around, and pushed my hand off of her. Clearly, she had been exposed to some really scary things. Her mother was likely a prostitute. It’s possible that she also prostituted Geeta. So she was really fearful. They said she cried every night. She had long crying episodes every day.

When I went back a year later she was smiling, and standing upright, and looking at people in the eye. And then when I went back again last year, she came running down the stairs and gave me a big hug, and was talking to me in English! She had never been to school before she came to Kutumb, and now she is one of the best students in her little private school. The Kutumb Project pays for a lot of children in the slum to go to these little private schools, because the government education is atrocious. So anyway, she came running down and she said ‘I’m so happy you are here!’, and gave me a big hug. And she’s not crying anymore. She has a family, she has a home, she has parents – Dr. Ashish and Puja – who love her and look after her and 29 other children in this little concrete building in the slums. And they are happy and healthy and helpful.

…It is such a joy to go back. Sometimes I go two years in a row, depending on what’s going on. But every other year, to go and just to see the children really blossom, it’s so powerful. And to see the women, with dignity, coming together as a group to talk about family planning or finances or different things. The kind of joy that they have as a result of having these opportunities… it’s just so gratifying. I wish I could take everyone there to see it. Because I feel like anyone who sees it, would do whatever they could to help.”

–Katie Kirkpatrick is Vision Builders Co-Founder and Board President. She and her husband have spent more than 20 years initiating charity efforts in America and abroad. In 2001, they began supporting charitable projects abroad which led to the founding of Vision Builders. Vision Builders was inspired by the desire to help children marginalized by poverty to access basic health care, nutrition and education.

The Kirkpatricks believe that it is possible for everyone to help in some small way, and that education and access to resources and information are essential to bringing long-term benefit to people in impoverished and unstable regions.

Another Year, Another Success!

The Vision Builders 6th Annual 5k took place on Sunday, September 16th this year. It was a bright, shiny, day and so much fun for all. Thank you runners, walkers, sponsors, fundraisers and volunteers for another great race!

Together we raised over $30,000 for the Kutumb Project, providing education, nutrition, safe housing and more to some of the world’s poorest kids.

For 5k Run & 1 Mile Results visit Everal Race Management (click here)

Click Here For A Video Slideshow, Compiled by Michael Samuelson .

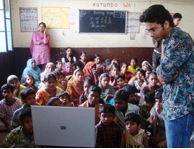

Saturday at Rameshwaram – Kutumb Village Clinic, January 7, 2012

Sarah Messer is a poet and a poetry professor at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington. She is also a dedicated Vision Builders Board Member and volunteer who donates several hours of her time each week to grant writing on behalf of our partner program, The Kutumb Project. To better understand the amazing program that she presents to potential grant makers, in February she accompanied Board President, Katie Kirkpatrick, on her annual planning visit to the program.* Below, Sarah shares her recollection of a day-trip they took from the Kutumb location in the Varanasi slum to the nearby village of Rameshwaram: site of the new Kutumb Village, which is under development thanks to our many generous supporters.

I am very grateful to have had the chance to travel to Kutumb and meet Dr. Ashish and Puja and all the Kutumb children, staff, teachers and volunteers. One of my favorite memories is our day-trip to see the progress of Kutumb Village, located in the town of Rameshwaram, about 15 kilometers from Varanasi and the Nadesar slum.

I am very grateful to have had the chance to travel to Kutumb and meet Dr. Ashish and Puja and all the Kutumb children, staff, teachers and volunteers. One of my favorite memories is our day-trip to see the progress of Kutumb Village, located in the town of Rameshwaram, about 15 kilometers from Varanasi and the Nadesar slum.

It was January in India and the air was cold and damp. We set off mid-morning–Dr. Ashish, Puja and their son, Manas, Vision Builders President, Katie Kirkpatrick, her daughter, Ryan, her Varanasi friend Geeta and me. As we approached Rameshwaram, the paved two-lane street crowded with limping dogs and beeping motorbikes narrowed into a one-lane dirt road that wound through the village. We passed stucco houses with corrugated tin roofs sitting right next to the road. As we moved into a more rural area, we passed a cow, then a calf tethered in a yard. There were dung patties spread on the sides of the houses to dry or arranged in patterns on the ground like fish scales. And everywhere the smell of dung burning, which smelled like earth burning. The threads of white smoke braided into the constant noise of accelerating scooters, of radios playing Indian music, and the sounds of unfamiliar birds. We passed water buffalos, bicycles, bamboo, fences made of tied up sticks, laundry hanging between trees.

The road narrowed even more as it exited the village center and entered fields, green and squared off—the road seemed to float above them. Two cars could not pass side by side. Yet we passed some people on bicycles, women walking through muted sounds of villagers talking between houses, someone banging sticks. In the distance the trees were scattered in clumps between the bright green fields.

Driving along the (now country) road I could see, through the scrubby trees, the occasional piece of walled-off land. A perfect and solid newly built brick wall, ten feet high or so. Kutumb Village is also one of these—a squared off place with a big brick wall and one entrance. The wall is topped by a curled strand of barbed wire. “Site for Kutumb Village,” the sign said. And just like that, we were there.

As we all stepped out of the car, I could see across the wide expanse of the campus some men smashing up bricks. They were working on another building project—the flooring and base of a building—over which they would then pour cement. A tractor with tinsel ribbons hanging along its cab sat empty next to a giant pile of dirt. One worker holding a shovel stood waist-deep in a hole out of which a web of tunnels led, the beginning of a foundation. A small grassy pond sat in the middle of the complex, and a rectangular garden of zinnias had been planted over by the recently opened health clinic.

Normally Dr. Ashish visited the clinic once a week on Sundays; today was Saturday. Still, more than 30 people found out about the date change and traveled to see him. Later he told me that 60 or more people usually visit the clinic each Sunday. “So,” he said, “Today is not typical.”

How did they know to come? I asked.

Word of mouth. Word reached 50 km away for one family: a woman with her four year old boy had traveled this far to stay with her mother in the neighboring village in hopes of seeing Dr. Ashish. Many others also traveled great distances because the Kutumb Village clinic is the only source of reliable free medical care in the area.

Dr. Ashish and his assistant, Javed, sat in the small square room at a simple desk. The clinic was spare and swept clean a makeshift examining table with a stool for patients to step up on, a bathroom scale, a metal cabinet containing boxes of donated medicines, ayurvedic mostly. A small shrine sat on a shelf recessed into the wall next to Dr. Ashish’s desk. The altar contained an image of the goddess, Saraswati riding a swan above a row of small offering bowls.

An elegant man with his head wrapped in a mustard-colored scarf stood at the doorway to ask patients’ names and their ailments, and give them a numbered chip the size of a button on a woman’s winter coat. Then they waited on the benches, against the wall, or next to the door with the morning glory vine winding up the side until their number was called.

When the patient’s number was called, they entered immediately and sat in a chair facing Dr. Ashish. He asked them many questions about how they were feeling. He took their blood pressure. He asked them to stand on the bathroom scale.

Most who attended the clinic that day were women; they arrived wearing brightly colored saris wrapped in heavier wool blankets, having walked without carrying much food or water. When they entered the clinic, their feet were bare, the soles painted red, adorned with toe-rings, shoes left outside on the folded burlap bag that served as a doormat. They entered with their arms thick with marriage bracelets, holding their number.

Their list of maladies: hypertension, sinusitis, headcold, ear infection, sore throat, jaundice, arthritis, asthma. The most common ailment of Indian women, Dr. Ashish told me later, is severe iron deficiency-anemia. It’s a cultural problem, he said; the women always eat last, after the men and children, and when people are poor, sometimes there’s no food left for them, or nothing of any nutritional value. And so, the women suffer and are tired all the time from being anemic, yet they still continue to work most of the day and night.

Two old women entered together in their gold bracelets and rings, their bird-like shoulders. One had a very bad ear infection; the other hypertension—her husband had died the week before. They followed each other in the door, one standing behind the other as if a shadow. Then one moved to the chair beside Javed as he counted out the medicines, cut off doses with scissors and wrote the script, placing the various pills into an envelope. The woman sat and put her hands together like a steeple, each finger touching its mate lightly. As if she was sleeping or moving slowly through a dream filled with honey. She rested her forehead against the roof of her hands, while her friend leaned into the stethoscope and Dr. Ashish spoke in his clear and proper accent, softly as if the whole room were falling asleep, he leaned into both of them asking what was wrong.

What was wrong, I would learn later, was probably more than just a physical ailment. Because becoming a widow in India changes everything about one’s former life. In many cases, when the husband dies, the widow’s children toss her out. Widows are considered bad luck, a bad omen; they are not invited to weddings, not allowed to hold infants, or to attend celebrations. The mortality rate is 86 percent higher among elderly widows in comparison to married women of the same age group. As widows, they are living what some call “sati” or the practice of burning a widow alive with her husband’s corpse; except they are burning metaphorically, dead to their family and former life. They shave their heads, wear only white, strip themselves of any jewelry or color. They eat only one meal a day. Widows are sometimes called “pram” which means “creature” because she was only human in relationship with her husband—he elevated her from a creature to a human—but after his death she becomes a creature again, referred to as “it” rather than “she.” When her husband dies, she is supposed to give up all earthly pleasures, to be “devoted to her husband in life and death.” As it says in the famous Hindu text, Skanda Purana, widows are “more inauspicious than all other inauspicious things.”

All of these reasons, mixed with the sheer grief of losing a spouse, seemed to be the cause of the widow’s hypertension. Dr. Ashish told her that she should rest and try and eat more than one meal a day.

More women came into the clinic, some with children, some without. Dr. Ashish asked them all to sit by him in a chair as he took their blood-pressure, listened to them breathe with his stethoscope. He gently supported their arm, leading them onto the scale. It went on like this for two or three hours.

The woman who walked 50 km carrying her four-year-old child also carried an X-ray with her when she entered the clinic. She arrived with the child’s grandmother who wore a wrinkled face and a bright sari. The mother handed the child over to the grandmother, then pulled the X-ray out of her bag and handed it to Dr. Ashish. Against the light of the window, Dr. Ashish stared at the image of the child’s spine. The boy wore thick cotton pants. Someone had put his hair into pigtails so that he resembled a girl. The child was four years old but was the size of a two-year-old. It occurred to me that this mother must have carried her child the entire 50 km. He couldn’t walk. Someone always had to carry him. Ashish lifted him onto the waist-high table and examined him, moving his legs forward and back, gently rotating them. Then he held the child’s arms, made him stand up, stretching the boy’s arms out and balancing him as he swayed back and forth. The boy’s body seemed floppy as if made of rubber. He whimpered and collapsed into a squat, sat down.

Katie then joined Dr. Ashish and together they lifted the boy off the table and encouraged him to walk, holding him by the arms. The boy’s legs went limp but he managed to take a few steps. Dr. Ashish and Katie encouraged him. What the boy needs, Dr. Ashish said, is physical therapy. At one point he had weak back, a gap between two vertebrae, but it wasn’t causing him to be paralyzed, Dr. Ashish said, what he needed was exercise. His mother probably tied him to her while she worked, or sat him in a corner. She carried him everywhere, said Ashish. And so there was no need for him to gain strength and over-come his weakness. Dr. Ashish gave the mother a series of exercises she must do with the child every day.

Is there any difference, I asked him, between these people in Rameshwaram and those in the Nasdesar slum? I asked mainly because I have never watched him care for people in the slum, though I have seen his tiny office, which is even smaller than the room we were in at Rameshwaram. Yes, he said, there is a big difference. Namely, he said, it’s the follow up.

“I know I will see all of these people again,” he said, “they will follow my directions and take their medicine when they are supposed to. If I tell them to come back in two weeks or a month, they will come back.”

And the people in the slum? “Not so much. No follow-up,” he said. According to Dr. Ashish, the patients who visit the slum clinic only want a one-time fix. Most of the people he saw never came back. People in the country are still very poor he said, but it’s different. Yet, regardless of this difference, Dr. Ashish is committed to helping all patients–in the slum or in the countryside.

The countryside is not without its obstacles. It turns out that the villagers didn’t like the wall. Even though it was common in the area, they didn’t like it. And often village elders told the caretakers different information, perhaps their opinions verses what Dr. Ashish had decided to do. “We have to work hard to have good local relations,” he said. They had to watch over everything. And no one is more watchful than the locals. It’s a benefit to have them think they are responsible, Dr. Ashish said, always positive.

Ryan, Geeta and I decided to go for a little walk down the road to see where the locals lived. Outside Kutumb Village’s main gate, the road moved one way towards squared off green fields and trees; the other way back towards the village. When we went this way we immediately came upon a neighboring house with a car in a square dirt yard, a cow and a calf tethered, lying down and chewing their cuds. This way there seemed always to be a dog standing in the road, its back legs hunched, its body worn out by fleas. This is the way the women walked home, past the “Site of Kutumb Village” sign and these dogs; back through the winding village with all its small fires and deep rutted roads raised above wet fields, dung spread on the sides of houses to dry. There were also thatched three-sided buildings that sat like garages with their doors wide open. At night, small fires or candles would be lit in the openings, making every house glow from the inside like a giant lamp.

But in the other direction, away from the village, there were very few buildings at all, only walls and squared off open land. Here Kutumb recently bought another plot of land also fenced by brick but unmade and swampy, some kind of thick grasses planted there as a crop and the wild mustard grown up neck-high in the back acre. Beyond this, another, higher road where a boy wearing a bright red shirt pedaled by on his bike. He straightened his knees on the pedals when he saw us, stood up and coasted. This is where Dr. Ashish will eventually plant a vegetable garden to feed the children of Kutumb Village. Farming and gardening vocational training is also in the works – the students will learn how to read and write in the classrooms, but they will also gain important farming and agricultural skills to assist them in their future lives.

As we walked back to the clinic, the last patients were just leaving. The man in the mustard-colored scarf was escorting them out the door. Puja had brought some chairs into the clinic and a small table that seemed to have appeared out of nowhere. She carried in two large thermoses of the best tea I had ever tasted – warm and spiced with milk and sugar. We all sat very close to each other around the small table – their son, Manas, back from playing in the sand pile, squirmed on Dr. Ashish’s lap – and we drank tea out of small paper cups and ate biscuits called “Nice Time.”

And it was. As I looked out the window driving away, I already missed it. And I thought about how nice it would be when all the Kutumb children will be living here. And how nice it will be to some day return.

###

International Women's Day

March 8 is International Women’s Day. Kutumb had a special picnic on Women’s Day to celebrate the women in their program!

By honoring and advocating for women in some of the most impoverished areas of the world, long-term sustainable social change is possible. Each year the United Nations focuses on a special theme for Women’s Day to reflect global and local gender issues. The United Nation’s Theme for Women’s Day this year was “Empower Rural Women – End Hunger and Poverty”.

“Rural women are active agents of economic and social change and environmental protection who are, in many ways and to various degrees, constrained in their roles as farmers, producers, investors, caregivers and consumers. They play crucial roles ensuring food and nutrition security, eradicating rural poverty and improving the well-being of their families yet continue to face serious challenges as a result of gender-based stereotypes and discrimination that deny them equitable access to opportunities, resources, assets and services.”

“Rural women are active agents of economic and social change and environmental protection who are, in many ways and to various degrees, constrained in their roles as farmers, producers, investors, caregivers and consumers. They play crucial roles ensuring food and nutrition security, eradicating rural poverty and improving the well-being of their families yet continue to face serious challenges as a result of gender-based stereotypes and discrimination that deny them equitable access to opportunities, resources, assets and services.”

Read more about the UN’s vision and plan for rural women in all nations.

Vis ion Builders is honored and happy to help support the Kutumb project, and the work the Kutumb Project does EVERY DAY to empower women and girls in many core areas – such as access to education, health care, access to resources, and food security.

ion Builders is honored and happy to help support the Kutumb project, and the work the Kutumb Project does EVERY DAY to empower women and girls in many core areas – such as access to education, health care, access to resources, and food security.

Happy Women’s Day, every day!

Happy New Year Kutumb

Vision Builders’ Board President and Co-Founder Katie Kirkpatrick just recently returned from India, where she visited Dr. Ashish, Puja, and the children at Kutumb. Katie met with the Kutumb staff to review the project’s accomplishments in 2011, and to discuss needs and goals for 2012.

Regarding the Kutumb shelter located in the Varanasi slum, Katie reports, “Everyone at Kutumb is doing splendidly. The children are all so happy and healthy and well-mannered – such a contrast to what is going on right outside their door.”

Katie notes that there are still so many children in need, “…9 year olds are smoking crack and glare at you with contempt. There are 5 new children at Kutumb. One 5 year old girl showed up in the middle of the night when police arrested her criminal/prostitute/addict mom and left her alone. Her name is Guriya and she is a little ray of sunshine who loves to dance.”

There is clearly so much need for the services provided by Kutumb. The Kutumb project expansion is still in progress as we continue to help raise the needed funds. This trip included a visit to the land which Dr. Ashish has purchased for the new Kutumb Village. Says Katie, “It is a perfect spot and will make a beautiful home for the children. It is in the midst of a very poor village and Ashish has started a free clinic there in a previously existing building.”

One hundred or more people show up every Sunday to see Dr. Ashish, many of them elderly widows who walk for miles to get there. This 80 year old woman (pictured left) had a terrible middle ear infection and had been in pain for a month. Katie explains that the situation for widows in India is truly awful: “Often they are homeless because their children won’t take them in and if they live with their children, they are only given food if the rest of that family has eaten and there is food left over.”

The next Vision Builders board meeting will include a review of 2012 fundraising priorities and goals for Kutumb. We wish you all a very happy new year and we thank you for all the wonderful support you give to Vision Builders.